Finding Heaven in the Holler

I discovered Shelby Lee Adams’ work in the gift shop of an art museum. His photography book, “Salt and Truth”, was featured on a shelf full of classic art volumes. I spent 2 hours on the floor of the gift shop looking through his photographs. His roots were my roots and his photographs took me back to my childhood visits to the hollers of Paintsville, Kentucky. My dad grew up there, I didn’t. My grandfather worked in the coal mines. My dad joined the marines to escape all of this but going back always reminded him that the mountains never leave you even when you leave them. Shelby’s photographs are not scenes from a film but pictures of life in the most real place you will probably never know…unless it’s in your blood.

Your first photograph and its significance?

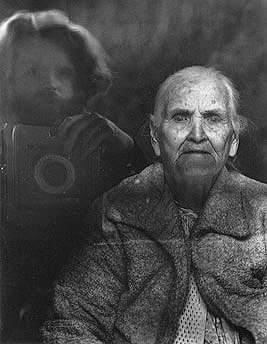

I think my grandmother’s blindness was the source of my visual arts pursuits. She was going blind when I was just 8 years old and by the time I was 12, she was totally blind. I loved my grandma. Her experience affected me deeply and I’m certain this eventually lead to my becoming a photographer. Grandma had an optic nerve disorder where her eyesight slowly dimmed into total blindness; nothing could stop this. At that time, I drew in sketchbooks and painted with watercolors. My mother encouraged my artwork from an even earlier age. We stayed with my grandparents often; they lived on a farm in Eastern Kentucky with cows, pigs, horses, chickens, and fields of corn and potatoes. Later, my grandma became the first person I photographed.

We would walk together, strolling around the farm, gathering hen eggs and feeding the chickens, watering the cows, and doing other farm chores. When something caught my attention, I would stop and sit then start sketching and drawing. Grandma was very patient with all of this. When back home, she would lie down on her bed to rest and ask to see my drawings. I would get a lamp and hold it over my sketchbook so the light was bright. She so enjoyed my artwork. I thought if I just learned to draw better, become a skilled artist, then maybe that would save my grandma’s eye sight. My mother continued to buy me art books and art supplies and I remember copying Michelangelo’s angels. Everyone enjoyed seeing those drawings, but grandma still went totally blind.

As a child, I focused on making art as a way to heal loved ones or to touch others and share compassion. That stayed with me. When I attended art school at age 19, I discovered photography. Returning home, my first photo essay was about my grandma and her life on the farm. I’ve always believed that photography serves a purpose beyond just recording or documenting.

Shelby Lee Adams and his Grandma

You are connected to your subjects. Does that make photographing them more difficult?

My native region became my photographic pathway to explore what and where we all came from and how we are all related. Throughout my teenage years, the media and news from the mid 1960’s through the 1970’s exploited our culture’s needs, searching for stories from then President LBJ’s “War on Poverty.” Locals grew tired of the poverty labels put on all of us by the media’s demands, illustrating our government’s new programs. I traveled with my parents, who worked out of state. When we returned home, sketching and drawing was how I got to know people while learning to express myself … photography came later. I always visit and ask permission before exhibiting my friends’ pictures. My photography is personal and indifferent to media coverage. I had to leave the area to work but I always returned to make new photos. I give out pictures to everyone previously photographed and I send copies of my books back to the families. This has always been my way of sharing and staying connected.

From year to year I still return and photograph many of the same families, each time finding someone new and often growing closer to old friends. The difficulty comes when I hear stories of family and community disputes, corruptions, abuse and manipulations. The holler people often get taken advantage of because they have few defenses. I think of my approach to portraiture as an ongoing conversation that captures the inner mood and feelings of a given moment. And sometimes, that is a very intimate and fragile time.

I ask people to tell me their stories and experiences and at the end of their narratives (both positive and negative), we make photographs. Sharing and understanding parts of another’s life influences and makes an imprint on the outcome of the photographs. Part of their situations and experiences are hopefully expressed and transferred subliminally and unconsciously to the viewer. That to me is powerful and purposeful. Often, the factual story cannot be told or published, because this can embarrass or even cause harm to the person living in the community. Together, my subjects and I must feel satisfied with the photographs and words shared in my books or articles, before publication.

The viewer can experience another’s circumstances and vulnerability more responsively by choosing to look and connect with the photos. Pictures reveal not only others to us, but how they are regarded and treated. For me, portrait photography is a study of our behaviors and actions bonded together. How we live our lives determines and affects how our neighbors live… to some extent.

Back home, the wealthy (and we have plenty), isolate themselves and the poor multiply and separate in the hollers while our government regulates support. In trusting relationships, photographing any specific group over time, will mirror back how one looks, how the world and one’s own people see and regard each other without the subjective need of a written narrative.

In our region, the media often blamed poverty. We are as we are, often overly clannish or economically segregated from each other. We go to town but we sometimes don’t see each other because shame hides and distorts our sense of common ground.

Mountain and holler people tell me they love their privacy and isolation, it is mostly self-imposed and represents a freedom that most of us do not know. Today, if you need and receive government assistance in any form, you have others viewing you critically. For example: A local mountain mother describes her court appearance when a social worker required her family be taken to court because of alleged child neglect: “When we went in front of the judge, the judge acted like we wanton’ there, like we wanton’ even in the courtroom. Wouldn’t look at us. The social worker told us, the judge will’ do what we want.” That is the problem. Many locals have grown to resent seeing those in poverty. Some have become conditioned to ignoring the poor, abandoning their empathy and compassion for others. Many foreign governments often forbid images of their poor to be taken or seen. Sometimes, I wonder which is best?

I take all types of photographs. More frequently, I’m asked to photograph celebratory events or rituals… a new baby, wedding pictures, funerals, a father with his new car, a prize hunting dog, or children with their puppies and cats. In spite of what others may think, life in the mountains can be very joyous because there is a lot of diversity.

Scotty with Banjo

Your photographs capture the climate of Appalachia so well. It is almost like its own country. How did you establish trust with the families?

People proudly say to me, “You come back, others don’t.” My return trips help develop confidence and recognition from the people I know. Many in the hollers do not receive a lot of visitors. It is the groundedness, in these salt-of-the-earth people, that I love so much. They have so little yet they make do, survive, and sustain themselves for generations. They are such generous people. They are honest and open with me because I don’t betray their beliefs or embarrass them in my pictures and publications. This is an earned trust developed from years of returning, and that returning keeps opening new doors for me. The isolation of the mountains makes it appear as another time and place, but our region is an integrated part of America.

What do you want people to see in your photographs? What do you try to capture?

So much has been published and written about our area’s neediness. I see beyond that. I try to photograph the enduring spirit and souls of these people in a respectable manner. The people have their own voice too:

“There is no poverty to us; we’re rich in what we have and do. OK, so we don’t have a lot of money, we don’t have big fine cars and fine homes. We have tradition; we’re rich in culture. I can take someone from NYC and bring him or her here and they would starve to death, because they don’t know here. They don’t know how to survive, how to preserve food, garden, canning, how to get by from the land. That’s what we do. It’s not just a culture past; it’s a way of life now. It’s our way of life. I wouldn’t trade this, my way of life for anything that anybody in NYC or anywhere has.”

—Hobart White, Eagles Nest, KY

Have you ever stopped mid-photograph because you were overcome with emotion? I’ve definitely cried while looking at some of your photos.

My work is about visiting and getting to know families, so the photographs are often an afterthought or conclusion to an important visit. Timing in photography is important. I can’t photograph someone if I don’t have their interest and cooperation and at least a basic understanding of what is going on in their lives. So a story and event is shared first and then we photograph. The mood of the moment [during a visit] can affect how I place the lights, compose the frame, or ask my subject to sit or stand. I’ve had times when I needed to leave and come back in a couple days to make the photographs. Sometimes, you need to get a more objective perspective on how to visually portray another or their situation. You can photograph someone for years and still not understand or capture the essence of that person. I’ve also had times when a subject says, “I’ve waited years for you to take my picture.” You photograph them the first time and it’s a quintessential moment, never to be repeated again. Some folks have only one photograph to give.

What was the most difficult photo that you’ve ever taken?

I have chosen not to make photographs when I felt there was no dignity to portray, sometimes life can overpower one’s self-respect. So, I prefer to wait and make photos with some when they are sturdy. My manner and style of working is as a formalist, meaning I only photograph with my subject’s full corporation. A photojournalist works differently, capturing a moment or event as it’s happening. I work with my subject’s full knowledge, a camera, lights, and my subject’s involvement. I call my work “collaborative” because we work together to make the photographs.

Why do you feel such a connection with the people of Appalachia?

It’s my roots. My work is autobiographical in part, made in a complicated, diversified, and often misunderstood culture. I’m always searching for a deeper understanding of my people, my family, my community, and our place in the larger world.

What have you learned from your subjects?

That mountain and holler people are open and far more accepting of others than many give them credit. They are far more tolerant and receptive to another’s differences than mainstream America might think. As a teacher, I’ve taken my college students from New England and European exchange students to the heads of the hollers. Mountain people are curious about others and very friendly. They are not the stereotypes we often read about. If you are blood kin or just welcoming, you are often taken in and received, no matter what your background or look.

In Eastern Kentucky, we are mostly white mixed with many races: starting with native Cherokee Indian then Irish, Scottish, English, Dutch, and Italian. Later, we discovered that we were mixed with the Melungeons who were most likely African/European mixed-race unions.

When are we going to see that our mountain and holler people (those that society shuns), patiently and respectfully care for impaired individuals and families with dysfunctions?They have unconditional love for their fellow human beings. They hardly ever institutionalize regardless of disability. When will we recognize their devotion? Doesn’t matter if someone is blind, handicapped, peculiar, comatose, deformed, mental, or disabled in whatever way. Mountain people accept others with grace and kindness and they uplift the burdened in prayer to God. They sacrifice themselves nobly for all.

What is the most beautiful thing that you’ve ever seen?

Joy and happiness expressed in another’s face that may have next to nothing.

If you could create a short film based on your photographs, what song would be playing during the intro?

Beethoven

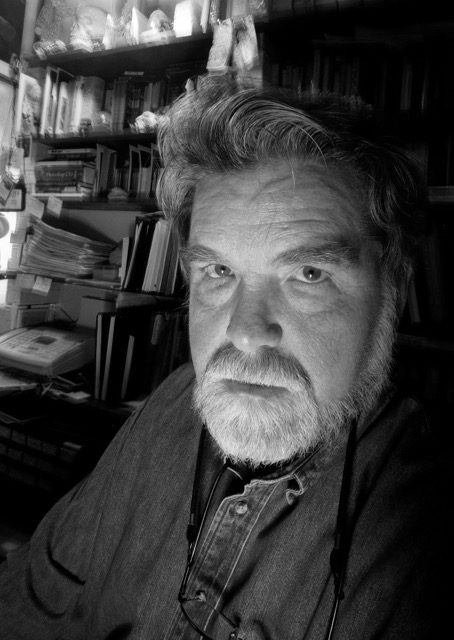

Shelby was born in Hazard, Kentucky. He has had four books published of his photography, all completed in his native region. His last published book is “Salt and Truth”. He is a National Endowment for the Arts and Guggenheim Fellow.

Shelby Lee Adams

Copyright ©Shelby Lee Adams, 2017

shelby-lee-adams-blogspot.com